Lecture highlights climate justice

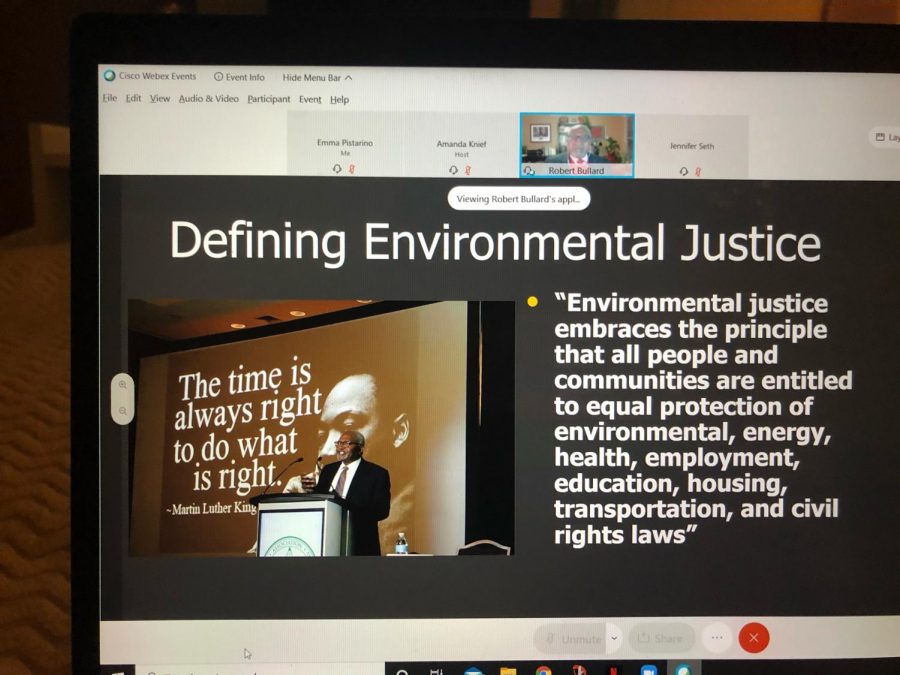

Robert Bullard, widely regarded as the “father of environmental justice,” discussed his work combating environmental racism as the latest installment in the Aldo Leopold Distinguished Lecture Series.

Mar 4, 2021

At 7 p.m. on Monday, March 1, Robert Bullard gave a lecture on “The Quest for Environmental and Climate Justice” via the virtual platform Webex, discussing his life’s work as well as the continued need to empower vulnerable populations in the fight against climate change.

The presentation was part of the Aldo Leopold Distinguished Lecture Series and was hosted jointly by Iowa State University, the University of Iowa and UNI.

Bullard is a sociologist, known as the “father of environmental justice,” who has been involved with environmental and climate justice since the 1970s. His work at Texas Southern University, where he is the former Dean of the Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs and a current distinguished professor, as well as his 18 award-winning books on the subject, have gained him recognition in the field. In 2020, he was awarded the United Nations Environmental Program’s highest environmental honor, the Champions of the Earth Lifetime Achievement Award.

As defined by Bullard, environmental racism refers to any policy, practice or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages individuals and communities based on color, whether intentionally or not.

“In the US, not all communities were created equal. Some communities are protected, some laws are enforced rigorously in some areas or neighborhoods, while in other areas government officials look the other way and allow operations to occur,” Bullard said. “If it happens to be poor people and people of color getting the worst of the worst, that is a form of injustice. This shows up in bad health, or environmental health disparities.”

During his hour-long presentation, Bullard described his role in the environmental justice movement, which began with the “Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corporation” lawsuit in 1979. This lawsuit, brought by his wife Attorney Linda McKeever, represented middle income black communities in North East Houston, who were fighting for equal environmental protection under the law.

Bullard’s work was able to prove that 82% of all landfills in Houston had been built in Black neighborhoods, between the 1920s and 1978, although Black citizens made up only 25% of the city’s population.

Although McKeever lost the lawsuit because she was unable to prove intentional discrimination, Bullard said he sees it as the beginning of an important movement of environmental justice and self-determination in the United States.

“We lost the battle but won the war in terms of starting a movement. The lawsuit, which came before other environmental studies at the national level, laid the foundation for environmental justice teaching, research, policy and civic engagement for decades to follow,” said Bullard.

Bullard went on to talk about the issues that minorities are still facing today when it comes to environmental and health crises, particularly related to the COVID-19 pandemic. He noted that Black children are already four more times to be admitted to the hospital due to respiratory illnesses like asthma, and a 2020 Harvard study showed that death rates for COVID-19 are 15% in people who breathe in high concentrations of air pollutants.

“Blacks and Latinos are disproportionately burdened with breathing air that has been polluted by whites,” Bullard said. “Black people in the US are exposed to 56% more pollution than what is caused by their consumption. This is unacceptable. And it is preventable.”

Bullard also pointed out that Black Americans are more likely to live in food deserts or lack transportation services, which forces them to travel further for COVID-19 vaccinations. This, as he sees it, is an issue of both transportation justice and health justice, both subjects Bullard has touched on in his work.

In the past year, however, he has seen community-based organizations working hard to help close this gap.

“I am optimistic that we will be able to achieve and address these issues in a way that will bring about justice and fairness for all,” Bullard said.