Preface

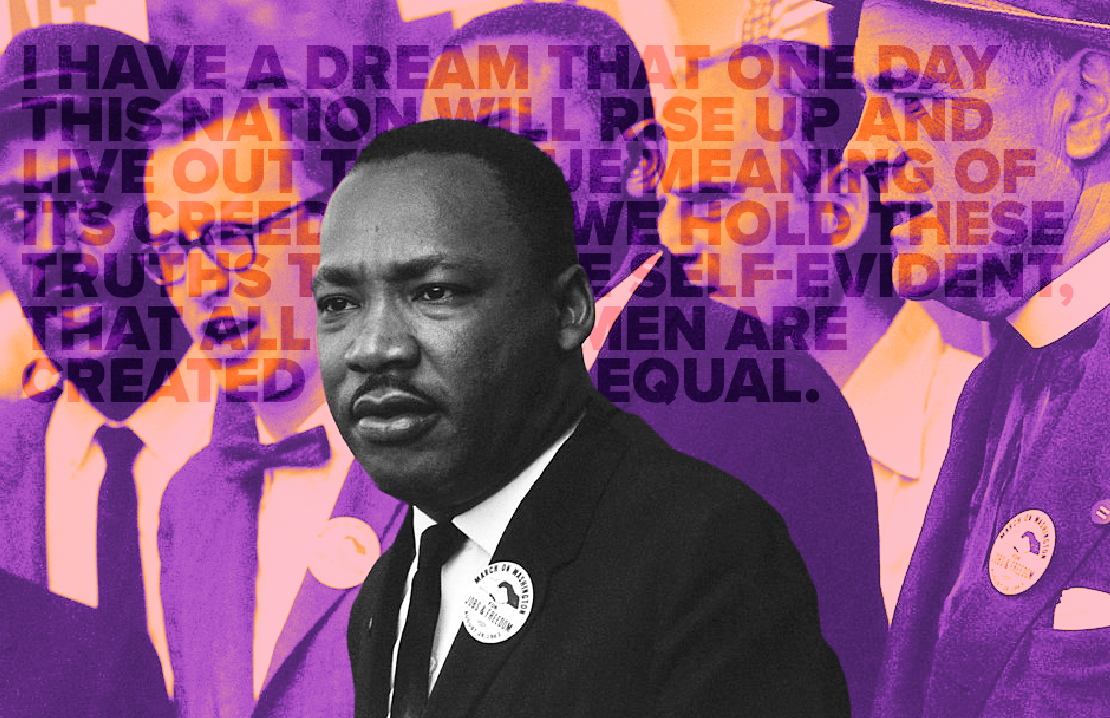

65 years ago, Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. visited the University of Northern Iowa’s Lang Hall Auditorium to deliver a speech regarding the Montgomery bus boycott that helped catapult the civil rights movement into motion. On Nov. 13, 1959, the Northern Iowan, then named the College Eye, published an article entitled “King Tells Bus Boycott to Full House on Wednesday,” providing direct quotes from King and a summary of his speech. Below is the full, archived transcript of the College Eye’s article.

Transcript

The story behind the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott was told Wednesday when the Rev. Martin Luther King spoke to a “full house” of students and faculty here. A summary of his speech follows.

Rev. King says there has been a radical change in the attitude of the Negro in the past years. The attitude by the whites in the past has been that the Negro is mere property, not a human being. The real tragedy in this is that it has given the Negro a false sense of inferiority and insecurity.

But, gradually, as the Negro became more literate, he began to take a new look at himself. This led to a determination to struggle and sacrifice until justice and freedom became realities – until the walls of segregation were crushed.

Before December 5, 1955, bus drivers referred to Negros as “black cows” or “black apes.” Negros often had to pay their fare at the front of the bus, get off, and board the bus again at the back. In the meantime, the bus might have pulled away with the fare, but without the Negro. When Mrs. Rosa Parks, a Negro, refused to vacate her seat for a boarding white male passenger in the section of the bus not reserved for whites, she was immediately arrested. Her trial was set for the next Monday. Between the time of her arrest, leaflets appeared telling the Negros to boycott the bus the day of her trial.

That day, the buses were empty of Negros, who normally contribute 75% of the passengers. The Montgomery Improvement Association was formed. Most of the Negro ministers of Montgomery are members of the executive board, and this was the steering organization for the boycott. A meeting was called for the night of Mrs. Parks’s trial, and the meeting place was filled to capacity. It was voted unanimously to continue the boycott until there would be more courtesy extended to Negro passengers; seats would be given on a first come, first served basis; and some Negro drivers would be on at least the predominantly Negro lines.

Fifty thousand Negroes decided to substitute tired feet for tired souls by walking proudly instead of riding in humiliation. The Association has to face the problem of how to get the ex-bus-riders around the city. Negro taxis agreed to transport Negro passengers for ten cents, but this only lasted three days, because the city commision placed a minimum rate of fifty cents for all taxis.

A pool of over 300 cars was then formed overnight. Stations for picking up and dropping off passengers were set up, most of them at churches. A system was worked out in just a few days that had taken the city years to form. Fifteen station wagons were purchased from donations from various companies.

The white reactionaries and the city government tried to negotiate a compromise with the Negroes, but all they would say was that the conditions asked for by the Negroes “couldn’t be met.” They brought in white ministers to discuss the situation who said that “It’s getting near Christmas, so let’s go back to riding the buses, pray, and think about the birth of Christ and everything will work out all right.”

False rumors were circulated about the leaders of the boycott, claiming that they were exploiting the Negroes and making thousands of dollars in the process. They tried to create jealousy by appealing with the older ministers, since most of the leaders were young men. The Mayor of Montgomery made a speech on television saying that the city government was “tired of playing around” and was going to “get tough.” Immediately following this, a series of arrests were made of Negroes for minor or imaginary reasons. All of these arrests only made the Negro community more determined to attain their objective. They were finally freed of their crippling fear.

From the beginning, the understanding of the philosophy of the boycott was nonviolent resistance. They refused to ride the buses, but they did it with love in their hearts, rather than violence. They tried to defeat a system, not individuals. “If the Negroes succumb to using violence, their chief contribution to posterity will be an endless night of meaningless chaos,” said Reverend King. “It is a question of non-violence or non-existence.”

In conclusion, he said, “The concept of understanding, creative, redemptive love which seeks nothing in return, which can love the person doing the deed while hating the deed was the center of the movement. We felt in our struggle that we had cosmic companionship – while we walked, we didn’t walk alone.”