Exceptionalism over acceptance

Oct 26, 2015

Who today is not familiar with the old joke that people tell about middle school? You surely have heard the complaint about the reward systems employed by middle schools – the students line up and, despite ability or accomplishment, are given awards for participation. I don’t know anything about pedagogy, so I won’t advertise my opinion on this specific practice. But I think that the sentiment that people feel about these practices is clear: why should anyone be rewarded for being average? What is the use in promoting mediocrity?

The answer that humanist culture provides for this question tends to be that “all people are created equal.” However, the praise of the adequate and glorification of the banal does not end in middle school. Even here, in the allegedly critical academia, enthusiastic support for the subpar continues.

It is difficult to attend three or more performances on campus during the semester without witnessing the sociological peculiarity that is the standing ovation. The experience for me often goes like this: At the end of the performance the artists bow and the applause begins. One, two or three members of the audience stand up and express their overwhelming satisfaction. And then, like ripples in a pond emanating from a disturbance, the audience stands in waves reaching backwards to the doors of the venue. When the wave reaches me I cannot help but feel an enormous pressure to follow suit and stand up.

I concede that even sometimes I give in to this pressure. In such cases, when I do stand, I feel dishonest. I feel dishonest, because my reaction is not for the benefit of the artist, but rather my offering to appease the beast of acceptance. I don’t want to catch myself doing this anymore, and I would urge my fellow student body to also abstain.

Now, I do not mean that it is never okay stand and give praise. I mean to argue that it should only be acceptable to stand and praise when you honestly believe that the work was worthy. I rightfully argue that it is often not the case; why else would people stand in waves? If a performance was truly worthy of a standing ovation, then the standing would be less wave-like and more rain-like; instead of people standing when others do, they would stand independently of each other as each individual becomes overwhelmed with the need to express their praise.

The student body is not the only group to blame for this behavior of praise, the faculty have also committed their fair share of acceptance-related crimes.

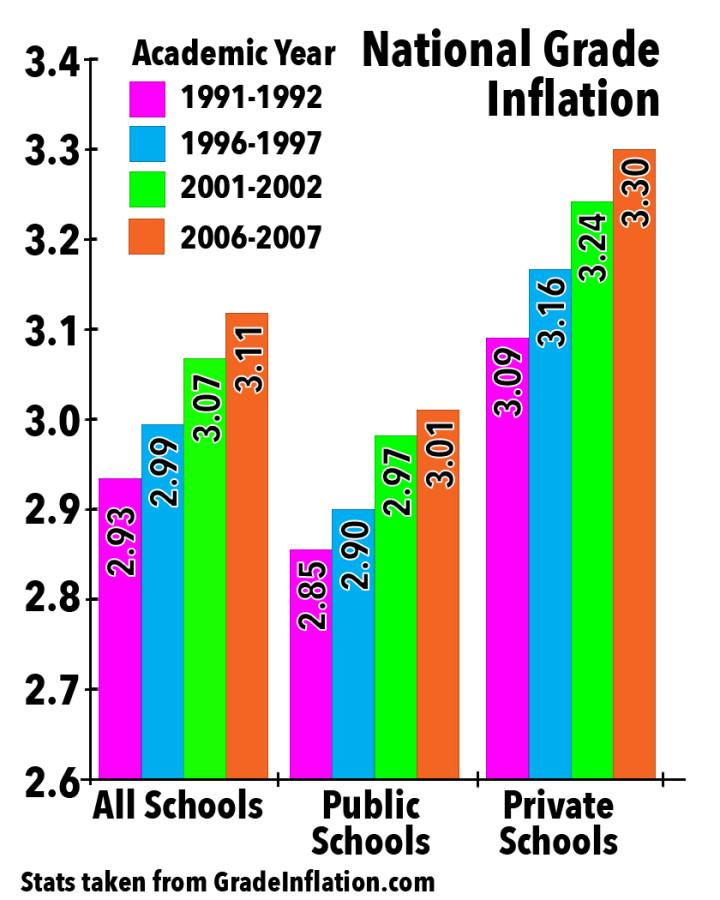

Grade inflation in the United States has been occurring since the 1980’s. The trend at UNI is an instance of this trend. From 1969 to 1986 the average GPA has remained between 2.72 and 2.69, respectively. From 1986 to the present, the average GPA has risen from 2.72 to 2.96. Grade inflation is a problem for a number of reasons.

First, grade inflation can give the wrong impression of one’s abilities. If a student obtains an B- in Humanities, despite deserving a C or D, then that student may continue doing this same amount of work as it is enough to get by. Secondly, if an A is easy to obtain, those who are motivated by maintaining a high GPA have little reason to perform above that mark. In this case the full potential of the student is not tried and reached.

In total, there is a devaluation of education. If institutions are reinforcing mediocrity, then what does it mean to have a degree? Why waste your time earning a certificate that is becoming easier and easier to achieve?

While it may be nice to repeat to ourselves “all people are created equal,” we admit that such platitudes are false when we engage in any form of contest. We understand that in the event of competition and struggle a victor will emerge, and we concede that it is likely that the victor will have traits which are superior to his or her competitors.

Although the human species no longer faces the same ancient forces of natural selection that our ancestors faced, we employ new forces in order to improve our culture and our behaviours. If the methods of our selection and reinforcement (grades and praise, for instance) are weak, then we cannot refine our techniques. What is the use of a broken sharpener to a dull blade?

I can understand how the objections might go. “Won’t someone feel bad if they don’t get a standing ovation, and someone else does? It isn’t right to make people feel bad.” or “Just because you lose doesn’t mean you aren’t valuable.”

To the first objection, I would argue that envy is a necessary positive force. Being envious is indicative of a disparity between your own ability and the ability of another. This revelation ought to be rejuvenating. Try your best to match or surpass that which you envy.

To the second objection, I would reply that the humanist mantra should not be “all people are created equal,” but rather it should be “all people are, at first, worthy of dignity and respect.” In any case, it is wrong to hurt someone’s development by falsely praising them when praise is undue: whether by giving them a passing grade or by standing up and clapping. Apply the following advice from Socrates, not solely to physical training but also to those core crafts and disciplines which appeal to you:

“No citizen has a right to be an amateur in the matter of physical training. What a disgrace it is for a man to grow old without ever seeing the beauty and strength of which his body is capable…” -Socrates