Religious freedom not discrimination

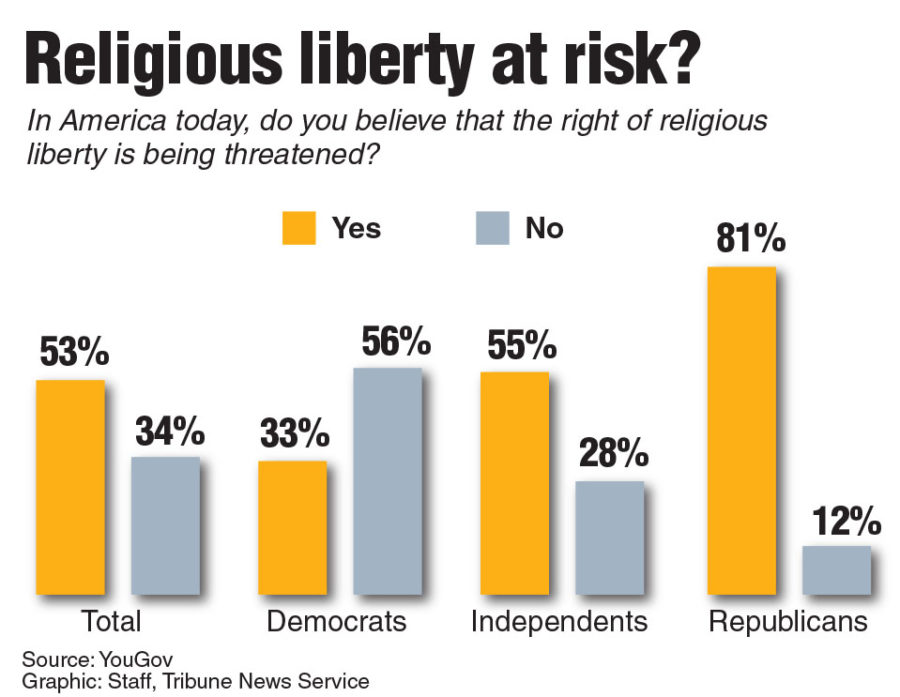

A 2015 study asked Americans whether they believe religious liberty is at risk. Day says we have the right to religious freedom laws are not discriminatory

Apr 25, 2016

In light of last week’s article on the rise of religious freedom bills and other similar legislation (Volume 112, Issue 52, Page 2), I’d like to do something rather unpopular on a public university campus and defend such laws, or at least their intent.

I’m in a unique position to write about this, as I studied constitutional law under Michael Farris, who basically named the original federal bill back in 1990s. It was passed by a near-unanimous Congress and signed by President Clinton.

There was a ‘yuge’ movement behind it, with evangelicals, Jews, civil rights activists and dozens of other disparate, usually opposing groups united to push back against a catastrophic Supreme Court decision.

In summary, the decision (Employment Division v. Smith) had the effect of reducing religious liberty to being a kind of second-class right by applying a less-stringent test to examine state action challenged on religious freedom grounds than on grounds of free speech, free press, or freedom of assembly, etc.

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act, at the federal and state levels, was a legislature-driven effort to rectify the high court’s error.

The singular motivating realization behind this effort was the understanding that religious people are religious in every aspect of their life.

Contrary to claims you might hear from secular critics, religion, properly understood, is not a hobby. It is not reducible to a weekly activity or even merely to believing there is something “out there.”

It is a way of life. It is a given set of principles, values and codes of conduct (rooted in particular beliefs about the spiritual realm) that have relevance for all of a religious person’s life.

To have religious liberty in any meaningful sense of the term is not merely to have the state allow a person to attend the religious services of their choice. It is to be free to live out one’s religious beliefs in specific, concrete ways as determined by the claims of said religion. It is to be free to live in accordance with one’s religious convictions.

There are, of course, long-standing, universally accepted limitations to this. A jihadist Muslim, for example, cannot claim religious liberty in the course of taking the lives of innocent people.

Private property is similarly sacrosanct in the U.S., such that there is no religious justification for stealing that will stand in the American judiciary. But the mere declination to participate in a particular economic transaction does not cross those lines at all.

This is not exclusive to conservative Christians, either. Robust religious liberty also protects the right of Jewish butchers to decline to prepare or transport pork to customers. It protects the right of Muslim business owners to close their stores during the day for their scheduled prayers.

It even protects the right of liberal Christians to decline to cater an anniversary dinner for, say, the county branch of the GOP.

This is not discrimination we’re talking about here. These bakers, florists, photographers, etc., that you’ve read about are overwhelmingly not bigots who put up signs in their storefronts saying, “We don’t serve your kind here.”

Perhaps the best example is Barronelle Stutzman, a florist in Washington state who had worked with one Rob Ingersoll for years before he asked her to service his same-sex wedding.

It was the only time there had ever been anything like a conflict between the two of them, much less any refusal to engage in commerce on the part of either. She declined because she wouldn’t /couldn’t utilize her skills to service an event she could not approve of due to the demands of her faith.

She had every right to do so, despite what her state now asserts.

Contrary to claims made in last week’s article, these laws are not an effort to prevent people from “being who they are.” If anything, they intend the exact opposite. Religious beliefs that stay in a one’s head and have no effects on how they live are useless.

They might as well not exist, and people would be better off not being religious in the first place. Ask yourself what that suggests about how (some of) the agitators decrying these religious freedom laws think about religious people.

Finally: the next time you hear someone (especially a progressive) scoff at the notion that doing business with someone constitutes any sort of statement of approval, ask them how they felt when they heard that Elton John performed at Rush Limbaugh’s fourth wedding in 2011.