Back to the basics of free speech

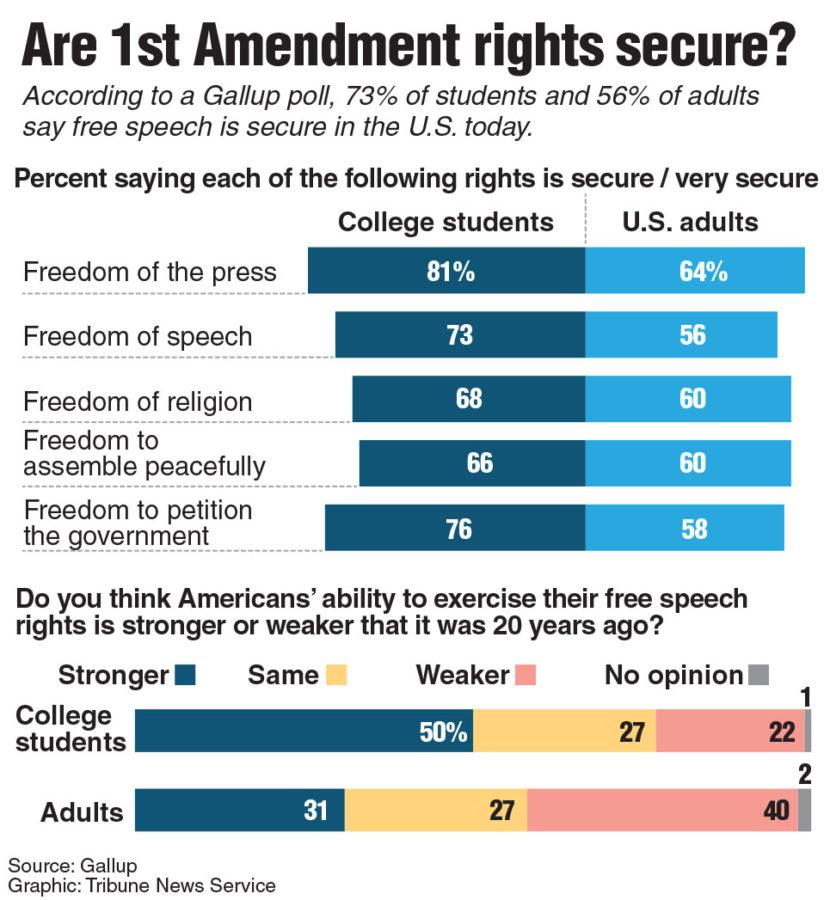

According to a Gallup poll from April, students are more likely than non-collegiate adults to believe First Amendment rights are secure in the U.S. today

Sep 19, 2016

Our campus has received a lot of talk about free speech, and what that means on a campus. This raises the question of what “free speech” is as defined by the Constitution, and what types of speech are legally allowed or disallowed.

In both 1798 and 1918, the federal government passed sedition acts that would make it illegal to critique our government in a way that would paint them in a negative light. Both were repealed shortly after ratification due to their dubious constitutionality.

For more information on these there are many sources, though our own university offers a Liberal Arts Core course on “American Civilization.”

To those of you who have studied defamation, sedition might sound similar, but there’s at least one important distinction. Defamation is a case where one entity paints another in a false light.

Light in this case is a statement which effects a person or entity’s face – the social currency of human interaction. Many have heard the phrase, “saving face,” wherein one would take an action not normal to their character in order to keep their reputation intact.

The spectrum of social light is built on opinion – positive or negative – and actuality – true or false. If someone was to attempt to create a comprehensive healthcare system, then saying that they had or had not taken this action lies on the axis of actuality. Whether or not a comprehensive healthcare system is a “good” thing lies on the axis of opinion.

Within this spectrum, libel – written or printed action – and slander – verbal or fleeting action – exist purely in the false-negative quadrant. In case you were wondering why this matters to free speech, defamation is grounds for a legal suit on behalf of the subject against the producer of the statement in question.

In order for legal action to be taken, the statement must not only be false, but it must have a negative effect on the subject’s life or livelihood. Effectively, the subject would be unable to save face without conceding to a falsehood.

UNI has earned a yellow light from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education – or FIRE, a conservative group funded in part by the Koch brothers – for our “Discrimination, Harassment, and Sexual Misconduct Policy.”

That policy prohibits creating a toxic “environment [which] may be created by verbal, written, graphic and/or physical conduct that is sufficiently severe, persistent, or pervasive so as to interfere with … the ability of an individual to participate in or benefit from educational programs or activities or employment access, benefits or opportunities.”

The UNI webpage for these policies reminds the reader that they mirror and are compliant with federal and state rulings on civil rights. Indeed, the policy also mirrors the definitions of libel and slander.

What happens when a person encounters discrimination? Adam Croom’s 2011 article in Language Sciences, titled “Slurs,” delves into an explicit aspect of this type of negative profiling by illustrating where it diverges from linguistically similar terms.

Croom outlines what are called descriptive words – “dog, woman, and African American” – and expressive words — “damn, bastard, and fuck.” One is pure description, while the other discloses a level of emotion or opinion from the speaker.

What’s interesting about slurs is that they blend the two types, Croom says. While a slur may be tied to a description of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc. it’s expressive of ideas and ideals – opinions – held by the speaker.

Just like slander or libel, the expression of these opinions can have a negative impact on a person’s life or livelihood based on false assumptions of superiority.

When one uses a slur or derogation to insult or to put someone down, they are saying that the subject is of a group inferior to that of the speaker. A racial slur implies inferiority of race as much as a sexual slur implies inferiority based on gender, sexuality, etc.

Publicly claiming that one race or gender is inferior to another – by direct slurs or other hate speech – lends pebbles, bricks and boulders to the mountain of inequality faced by marginalized groups, such as African Americans and women, face with issues like our current confrontation with institutional racism in police factions and misogynistic wage disparity in our professional world.

One argument against marginalized groups such as African Americans, women and the non-heteronormative masses would be the difficulty of a group claiming defamation against an individual or another group.

The quick response is that corporations have been filing defamation suits for years on the grounds that such acts injure the business, and by extension the employees from the bottom up. This is in fact a valid concern for many businesses who could be hurt by disgruntled former employees or competitors.

Unfortunately for marginalized groups, there’s little to no formal organization to them outside of severely underfunded and overworked nonprofit civil rights and equality groups. To put it simply, it’s easier for a company to fight for its rights than some people.

The perpetuation of bigotry through hate speech has led to readily observable instances which negatively impact the lives of millions of Americans – not to mention billions of people across the world – and it’s time to stop.