End of union rights discussed

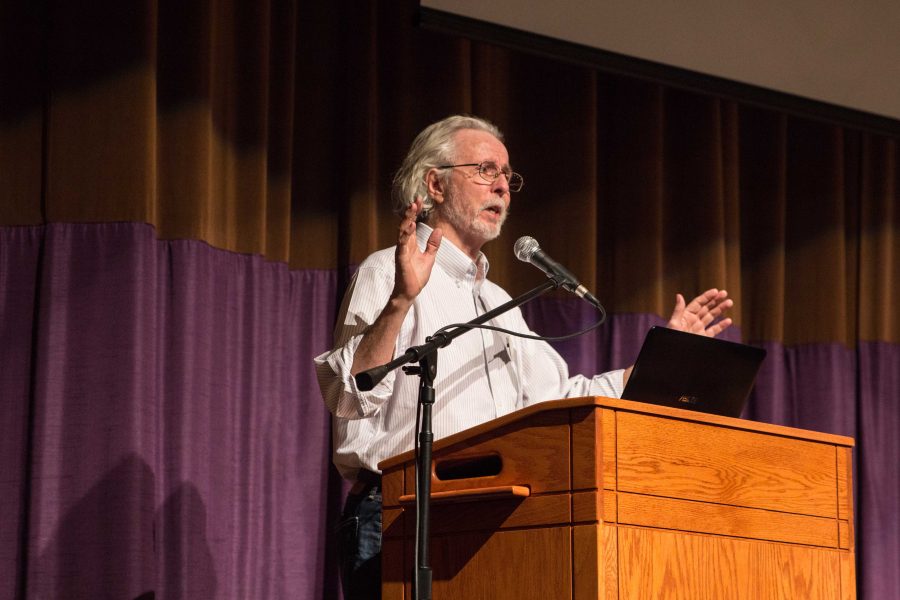

Joe Gorton, president of United Faculty, started off the meeting that occurred Friday, Jan. 27. He emphasized that this was a “crucial moment” at the university and that a multitude of issues could arise from changes that could be made to collective bargaining rights for public employees.

Jan 30, 2017

If university faculty lose their right to collectively bargain over health care, wages, working conditions and other benefits, students will bear the brunt of the impact.

That was the argument made Friday at the United Faculty’s Call to Action Meeting that took place in the Lang Hall Auditorium. Nearly 80 people — largely faculty — attended the meeting. Several students, Democratic lawmakers and UNI administrators were also present.

“This is the crucial moment in the history of our university,” said Joe Gorton, president of United Faculty (UF), UNI’s faculty union.

“The loss of our contractual protections could enable current and future administrations to impose unilateral decisions in a multitude of areas,” Gorton said in a press release forwarded to the Northern Iowan.

The release said future administrations could gain autonomy to reduce salaries, do away with evaluations (student assessments, evaluations for promotion, etc.) and lay off faculty with no avenues for the layoffs to be challenged.

Friday’s meeting was called in response to reports of the Republican majority state legislature considering extensive changes to collective bargaining rights for public employees currently outlined in chapter 20 of the Iowa Code — this includes university professors.

Changes reportedly being considered could mean that the faculty union would lose rights to negotiate contracts and disputes as they currently do — the administration and the union are contractually obligated to meet.

The current agreement has been in place for 42 years.

Becky Hawbaker, vice president of UF, said the union and the administration meet regularly to discuss faculty issues.

“I’m not kidding myself. They’re not meeting with us because they’re nice, although they are very supportive,” Hawbaker said. “They’re meeting with us because it’s ‘contract maintenance’ […] Without that contract, as nice as they are, they don’t have to choose to meet with us.”

Those who spoke characterized the potential bill as symptom of a larger attack on higher education; they supported that claim by pointing to a bill introduced a couple weeks ago by state Senator Brad Zaun, R-Urbandale, which seeks to eliminate tenure.

Jerry Soneson, department head of Philosophy and World Religions, said tenure is essential to retaining and attracting good professors.

He said the department is currently searching for a new professor. Each of the three finalists, he said, asked questions directly related to the tenure process.

“One thing that would happen if we lost our ability to collectively bargain is the possibility that we would eventually lose tenure,” Soneson said. “If we lost tenure, we would lose excellent faculty.” This includes the loss of current faculty as well as the ability to attract new, qualified professors, he added.

“This is every bit as important for our students as it is for faculty,” Soneson said.

Zaun told the Des Moines Register that the bill would establish “acceptable grounds for termination of employment of any member of the faculty.”

Gorton and others have said Zaun demonstrates a misunderstanding of tenure. The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) defines tenure as “an indefinite appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances such as financial exigency and program discontinuation.”

State Rep. Greg Forristall, R-Macedonia, told the Register that collective bargaining reform is being weighed in order to “give taxpayers a place at the table.”

He said the reform could protect against taxes being increased “willy-nilly every time there’s a demand from collective bargaining.”

Jennifer Schmid, executive director for AAUP, worked in Wisconsin when public employees there were stripped of their bargaining rights. She detailed how public universities responded.

“We’ve seen it’s not been a money saver in higher education,” Schmid said.

She said the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a prominent research university, had to pay $9 million, on top of salary packages, to keep 30 faculty members who were considering leaving.

Schmid said although institutions like UW-Madison had the financial means to keep faculty from jumping ship, others did not.

“What they saw with the four-year comprehensives, there’s 12 of those in Wisconsin, those institutions were just losing faculty— they didn’t have the resources to keep them,” Schmid said. “This ultimately is affecting the quality of education there. When you’re talking about a four-year comprehensive institution, if you start losing one or two faculty from a program you’re talking about certain courses or specialties not being offered anymore.”

She went on to say that this can mean B.A.-seekers may not be able to get their degree in four years. She said certain majors in STEM fields at the University of Wisconsin were taking, on average, six to seven years to complete their B.A. because of faculty attrition.

“That is just an untenable situation,” Schmid said.

Students detailed positive experiences with professors at UNI, and expressed concern that the loss of bargaining rights could mean the loss of high-caliber professors.

“I want to personally advocate for faculty as a student leader who is consistently empowered by faculty,” said Maggie Miller, chief justice for Northern Iowa Student Government’s Supreme Court.

“Thank you for all the countless hours spent caring for students,” Miller said.

Other students said if the quality of education at UNI is impacted it would directly affect students from Iowa, and in particular, rural Iowa.

Iowans accounted for 89 percent of UNI’s undergraduates in the fall of 2015 according to College Portraits.