Bill would require profs to disclose politics

Mar 6, 2017

An Iowa bill requiring Regent universities to hire nearly equal numbers of Democratic and Republican professors has been referred to the Senate Education Committe on Capitol Hill in Des Moines. State Senator Mark Chelgren, R-Ottumwa, introduced Senate File 288, which “prohibits such a university from hiring a person as a professor or instructor if the percentage of the faculty belonging to one political party would exceed by 10 percent the percentage of faculty belonging to the other political party.”

This proposal has been met with strong opposition by UNI faculty across campus. Joe Gorton, president of UNI United Faculty, called the proposal “un-American, unconstitutional and stupid.” Gorton labeled the bill fascist and in violation of the First Amendment.

“This is an attack against American democracy. It is an attempt to restrain people’s political ideas and identities,” Gorton said.

Many members of the faculty at UNI have called the bill unconstitutional, claiming that it is in clear violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, which states, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

Donna Hoffman, department head of political science, said the bill in question, if it were to become law, would infringe upon one’s right to association, of which political association is included.

“I’m under the understanding that right now they can hire people because of diversity,” Chelgren told the Des Moines Register on Feb. 20. “They want to have people of different thinking, different processes, different expertise […] so this would fall right into category with what existing hiring practices are.”

Chelgren did not return the NI’s requests for comment.

Associate professor of political science Christopher Larimer believes this requirement would undermine the hiring process significantly.

“You’re supposed to be bringing in faculty based on their knowledge and their teaching ability, their scholarly ability, in terms of producing research — that’s why they are hired. [Political ideology] has nothing to do with that.”

Hoffman admits that hyper partisanship has been increasing, but insists that ideally, a professor’s partisanship does not influence the conduct within the classroom.

“Just because I have a political affiliation, or do not have a political affiliation, does not affect what I teach,” Hoffman said. “It is a common trope that [universities] are indoctrinating students. We don’t go around creating Democrats here, or creating Republicans here or creating Socialists here; we are educating students.”

While the content has proven contentious, Larimer also identified a number of issues with the structure of the proposal.

“The bill has huge legal challenges, and almost equally large are the implementation issues with it. Because of those two things I don’t see the bill going anywhere. I’d be surprised if it makes it through a subcommittee,” Larimer said.

Hoffman added that if the bill passes, it would be difficult to enforce, especially considering one can change their registered party at any time, making the mandatory balance impractical to maintain.

The bill allows for university employees who do not affiliate with a party to report “no party,” in which case they would not be included in the recorded count of faculty composition. Hoffman, however, said that such a declaration has the potential to interfere with voting rights.

“In Iowa, we can participate in caucuses and primaries only if we are registered as a Democrat or a Republican,” Hoffman said. “Independents cannot participate in those events.”

One would have to change from a “no party” identification to either a Republican or Democratic identification in order to exercise their right to political association and, in turn, jeopardize their position at the university, according to Hoffman.

UNI students are also calling the merits of the bill into question. Austin Smith, a sophomore all science teaching major, said, “It’s a good idea in theory, but I would say it’s unfair to hire a professor based on their political party.”

Josh Brelje, a sophomore religion major, said, “I like the idea that there would be more representation from a conservative viewpoint in the classroom.”

Brelje said he has had professors who were clearly liberal and would like to see a better balance of political views on campus.

Jim Wohlpart, provost and executive vice president for academic affairs, feels confident in the range of voices currently at UNI.

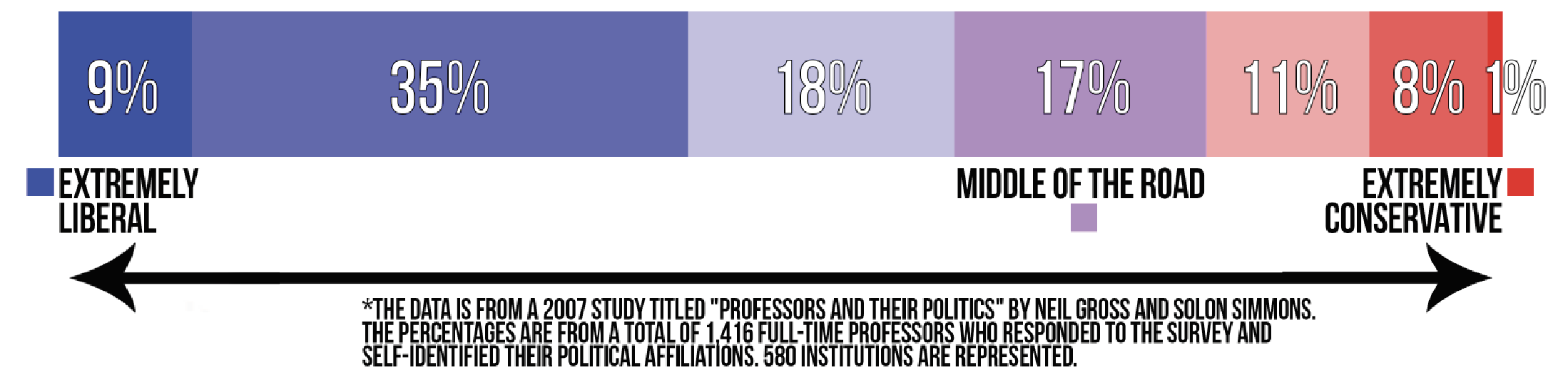

“I do know that we have faculty across the spectrum in terms of their political beliefs, and I welcome the diversity of thought and opinion on our campus,” Wohlpart said.

According to Wohlpart, UNI does not ask employees to report their political affiliations, and to do so would be unconstitutional.

Many members of the faculty doubt the bill has legitimate grounds to move forward, but still strongly oppose its enactment.

“This pretty clearly is not good public policy,” Hoffman said.

A similar bill was proposed in North Carolina but was dismissed.

Ryan Salucci • Mar 27, 2017 at 7:27 pm

As a conservative myself, who would love nothing more than to see a far greater representation of conservative ideas within the outrageously left-wing dominated world of academia; I must respectfully disagree with the premise behind enacting such legislature. Although today, professors and students alike are far more politically charged and outspoken in the classroom than they were a mere 5 1/2 years ago when I graduated from college; this is probably one of the biggest reason why I am thankful to no longer be in college. The solution to this problem in my opinion, is not to equal the political playing field, but to begin shifting focus away from the role politics plays in classroom, and back to the core meat of college studies which I believe is what college once was, and should still be about. This is not to say that political opinions and ideals do not take on an important role in a University discussion from time to time. But the unfortunately the now overwhelming tendency of political ‘opinion’ to take center stage in today’s schools has turned the once, fact-based learning experiences in the arts and sciences, into some sort of ideological boot camp. One in which of course, student are borrowing 10’s to 100’s of thousands of dollars to supposedly benefit their futures from.

Another important reason why I feel this policy is particularly damaging, is that it only serves to fan the flames of identity politics; an already out of control, and universally flawed concept which is slowly poisoning the fabric of today’s American society toward death. In only 2-3 short years since the concept first became a mainstream political topic, it has grown so completely out of control within our academic institutions that it has actually begun to erode the very foundation of what made higher education the once great experience that it has always, and should continue to always be.

Although the above article does not make any clear indication of which side of the political spectrum this idea is coming from, it seems fairly obvious that it is likely from the political right, perhaps with hopes to find a logical way to counter the extremely one-sided situation we already have among public colleges and universities. Again, I would love to see this happen. I am absolutely disgusted by the way the almighty “tolerant” left has openly butchered the concept of diverse opinion (something that matters a whole lot more than diversity of unchangeable biological features). I am disgusted when I am made to feel as if my valid opinions are vile and unwelcome by a person who turns around, only to preach to others that we need to be more open-minded. This needs to stop. But this simply is not the way to do it. A professor’s political background being used as a sort of affirmative action-based criteria for employment in order to even out a playing field, seems to me to be a tactic taken directly out of the liberal playbook of disaster. As a conservative I of course want my ideas heard and respected out of ‘true’ tolerance. But never at the expense of one of my most dearly held core American beliefs; to maintain and promote a system which relies strictly on equality of opportunity, and never on equality of outcome.