‘Bad Studies’ columnist responds

Apr 10, 2017

I have experienced more feedback from my article about sexual assault and bad social science last week than any other piece I’ve written.

First off, what took you all so long? I’ve made far more controversial claims in my past year as a Northern Iowan columnist (at least, I thought so, until this week), and I’ve faithfully made myself available for in-person discussion as described in my first column of the semester. All of three (you read that correctly) people have taken advantage of my offer. Where have you all been?

Much of the feedback has been either willful distortion of my claims, character assassination in lieu of an actual argument, outright lies or just plain nonsense that needs no response (“Re-victimization”? Really?) Yet in this sea of fury and falsehood, a couple islands of challenges are worth addressing.

In retrospect, some of my language choices opened myself up to criticism that at best distracted from the substance of my article and at worst made me seem ignorant and insensitive.

In my zeal to alert my readers to the reality of bad social science fueling nationwide panic over a nonexistent epidemic of sexual assault, I overlooked the technicalities behind the relevant terminology and (at least appeared to) unnecessarily disconnect rape from other sex-related crimes. That was mistaken, as it may have misled or confused some readers and unintentionally disturbed others, and I apologize for the lapse.

One would be mistaken, however if one took this to mean that my larger point (and indeed, my central argument) doesn’t still stand. It does (which is probably why the feedback has resoundingly failed to address it).

The original statistic of concern (“1-in-5 college women will be sexually assaulted”) still fails to meet the standards of reliable social science. The rhetorical game of “unwanted kissing” (for example) becoming “sexual assault” and then “rape” still plays out in public discourse, misleading the majority of people who (quite reasonably) don’t have the time or energy to verify it. At best the “1-in-5” figure only means “1-in-5 college women will experience some sort of forced or fraudulent sexual activity, from deception to emotional manipulation to physical coercion in all possible forms.”

Not only is that not a great sound bite (such that some activists have taken to saying verbatim “1-in-5 college women will be raped” despite it’s obvious falsity), but it still doesn’t take into account any of the other methodological flaws that plague virtually every one of these studies I’m criticizing (non-representative samples fraught with non-response bias caused by low response rates from self-selected respondents, etc.).

(For the record, all of these methodological flaws corrupt all other estimates found in these studies as well. The 1-in-71 claim for men, for example, is just as unscientific.) It turns out that even the researchers themselves are aware of their failures.

The sexual assault survey put together by the Association of American Universities (AAU) in 2015 led with the caution that the “1-in-5” figure is “not representative” of US institutions of higher education, and found that some of their own estimates were likely “too high” due to non-response bias in the sampling (as non-victims were far less likely to participate). Their cautions against hyping and oversimplification seem to fall on deaf ears, at least in the cases of activists, most journalists and many politicians.

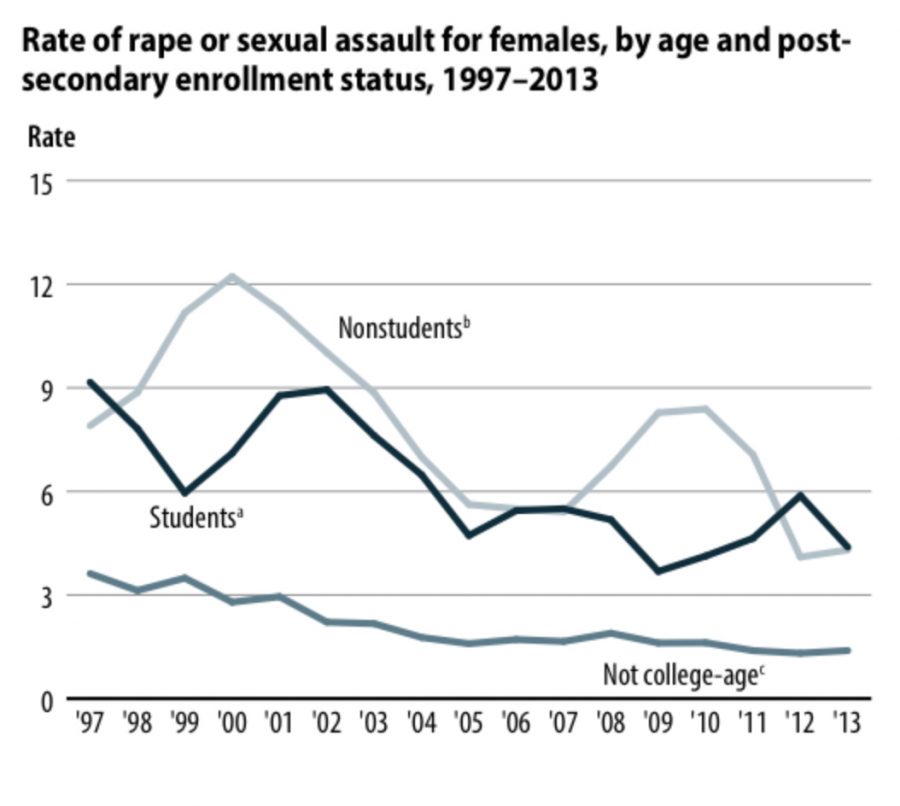

In light of these strangely pervasive methodological flaws (seriously, why is it so hard to find a study on sexual assault that doesn’t suffer from them?), the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) still reigns supreme as the most reliable set figures. The 1-in-53 estimate is confirmed specifically by the BJS’s annual National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) published in 2014, which maintains great methodological rigor by securing high response rates from large and truly representative samples of survey respondents, not by merely going off the number of reported crimes (contrary to the claims of one of my fellow columnists).

There are limitations to the NCVS (as there are in even the very best that social science has to offer), but it is still more reliable (which is the language I used in my initial column, by the way) than virtually anything else about which activists choose to make noise and over which media outlets write attention-grabbing headlines (and that’s why the NCVS is relied upon by the RAINN to the exclusion of most other studies and sources).

As I implied in my initial column, just one sexual crime of any variety is too many. But grouping them all together under a single estimate is misleading at best, and it contributes to (indeed, is arguably the source of) this nationwide panic about campus sexual assault under which we find ourselves. That in turn motivates measures like the kangaroo trials that are now frequently taking place on campuses, the unjust sanctioning of fraternities for the mere accusations against just one of their members, and lofty consent policies that essentially criminalize seduction among college students (looking at you, California).

My appeal is no different than in my original column: be more like the researchers, and not the activists. Do what you can to ensure that cool heads prevail over the hysteria and ideology that corrupt most sexual assault awareness campaigns.

I appreciate legitimate criticism of my argumentation and even my rhetoric. I don’t appreciate potshots at my graduate program, and at the faculty, students, and staff that comprise it, and I don’t appreciate the reduction of my opinion to my genitalia. I expected better than that, especially from my fellow columnists.

Ryan Hansen • Apr 11, 2017 at 12:23 am

“The rhetorical game of “unwanted kissing” (for example) becoming “sexual assault” and then “rape” still plays out in public discourse”

Unwanted kissing is in fact sexual assault, which, as defined by most sources including the US Department of Justice, “is any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient.” There is validity in you saying that not all sexual assaults are rape, and using the “1 in 5” statistic to talk about college women being raped may be an overgeneralization on certain campuses. However, it is important to note that while not every campus experiences this statistic, there still are some that do as mentioned by the AAU.

On the AAU, one thing to note is that their study only looked at “incidents involving two types of sexual contact (penetration and sexual touching)” as opposed to all forms of sexual assault.

“(seriously, why is it so hard to find a study on sexual assault that doesn’t suffer from them?)”

Because sexual assault is so varied and so unreported that it’s difficult for survivors to talk about it. As someone who has been affected by sexual assault in more ways than one, I haven’t reported any, nor do I feel comfortable talking about them, due to others’ and my own unwillingness to share information that personal. It’s difficult to talk about to my closest friends, let alone a complete stranger.

While you do mention that there are some problems with the NCVS, I think it’s important to mention a couple: a) that the survey lasts for three years with a given household with each member being questioned every 6 months only asking about events that occurred in the last 6 months, creating the possibility of a college participant or recent graduate in the survey to experience sexual assault outside of that time frame, and b) the lack of clarification as to what sexual assault entails, only stating “unwanted sexual activity” as part of the question.

“a nonexistent epidemic of sexual assault”

An epidemic is, as defined by Merriam-Webster, “something harmful that spreads or develops rapidly,” which is exactly what sexual assault is appearing as, even though sexual assault is not something new. Sexual assaults are becoming prevalent because people are starting to become aware due to the availability of the internet and advocacy. People are being made to pay attention to this thing that used to be shoved under the rug. About two-thirds of sexual assaults don’t get reported to police, based on statistics by the BJS. Yet even on our own campus look at how often we get emails about a transgression that occured. This is a real problem.

The issue I have with your articles is that there isn’t any reason to them. Yes, your point is that we shouldn’t say “1 in 5 college women are raped” because the widely varied facts due to widely vaired sources that are all faulty in one way or another due to the overall difficulty of the topic don’t support it. However, if me saying that there is a high chance that 1 in 5 women in college will be sexually assaulted (which even the CDC uses) gives someone the strength to recognize their sexual assault and start them on a path to recovery, then I’m going to say it.