Original play embraces authenticity

Feb 8, 2018

This past weekend, a darkened acting classroom deep in the basement of Strayer-Wood Theatre served as the backdrop for a tale of grief, addiction and familial instability.

“The Fair’s in Town,” an original play written and directed by UNI senior English major Colin Mattox, ran for four performances over the weekend, starting on Thursday, Feb. 1, and ending on Saturday, Feb. 3. The play was produced in collaboration with the Cellar Door Theatre Company and the UNI Student Theatre Association (UNISTA).

The play centers on Anita (Kim Groninga), a divorced mother of three who has invited her two daughters and boyfriend home on what would have been her son Jamie’s 25th birthday if he hadn’t died 10 years earlier.

Her daughter Marianne (Jen Brown) is a successful lawyer who is intent on convincing her mother to sell her house, while Anita’s other daughter Sophie (Jacqueline Kehoe) is a recovering drug addict who wants nothing to do with the past.

Simply put, both sisters cause tension with their grieving mother, whose relationship with her two daughters is tenuous at best.

Meanwhile, Anita’s boyfriend Red (Grant Tracey), a recovering alcoholic who is susceptible to sudden and violent mood swings, creates additional complications as an unwanted outsider amidst this emotionally damaged family.

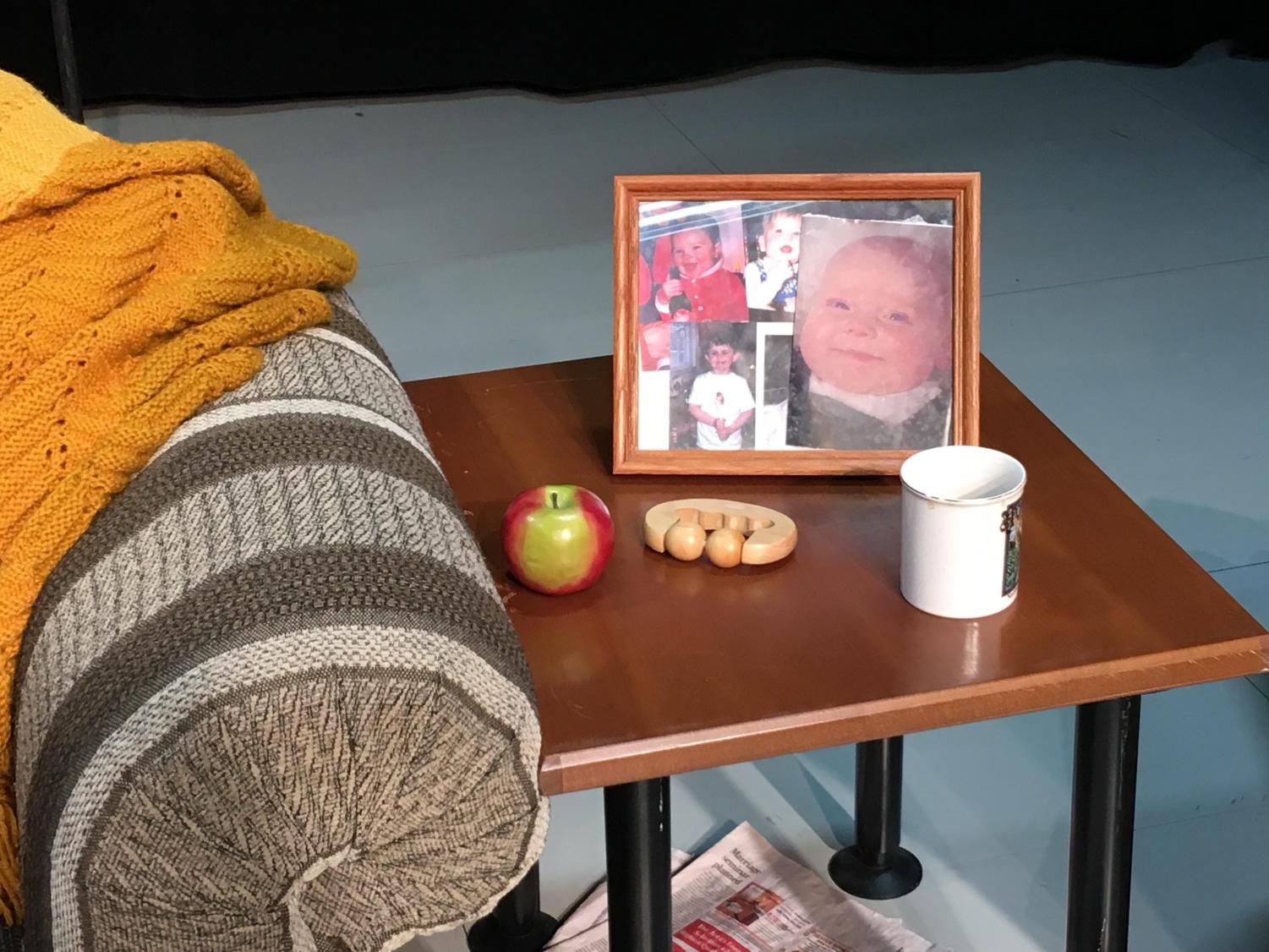

“The Fair’s in Town” follows a traditional three-act narrative structure, and all three acts take place in the same setting: Anita’s living room.

In a way, this minimalist approach to staging emphasizes the overarching theme of immobility present throughout the play, as the four primary characters find themselves struggling to move past their personal demons and/or guilt-ridden pasts.

In addition to this emphasis on stasis, the play’s limited setting lends a certain degree of intimacy to the production. As the audience becomes more familiar with Anita’s home and the characters that inhabit it, those same characters come to reflect this growing intimacy by gradually unveiling more of themselves to each other.

The setting, in effect, also mirrors the emotional and mental state of the play’s principal characters.

In fact, by the end of the closing scene of “The Fair’s in Town,” Anita’s modestly furnished living room is torn apart, with the various framed pictures of Jamie smashed against the floor and the broken shards of a glass plate littered in front of the audience.

To be sure, this lasting image of Anita’s home in disarray is a perfect visual encapsulation of the chaos in which Anita and her family find themselves. Just as Jamie’s baby pictures are forever damaged inside their smashed picture frames, so too are these four individuals’ lives irrevocably damaged as a result of their self-destructive and self-centered behavior.

And yet, despite their many flaws, all four characters in “The Fair’s in Town” remain incredibly sympathetic.

In other words, they are all undeniably human.

Much of the reason for the successful presentation of multidimensional and emotionally complex characters can be attributed to Mattox’s polyvocal narrative. Indeed, Mattox provides all four of his characters with multiple opportunities for moments of introspection and self-revelation.

At the same time, these moments of introspection, while occasionally mawkish, largely come across as authentic. This is mainly thanks to Mattox’s willingness to explore the unglamorous sides of his characters to reveal their innermost — and often ugliest — truths.

If there is any criticism to be made on Mattox’s script, however, it is that the play’s closing monologue, while emotionally poignant, did not feel entirely cohesive.

Perhaps this was due to the climactic final scene’s inescapably abrupt nature, but this disjointedness could have still likely been avoided through more frequent, albeit subtle, instances of foreshadowing.

Additionally, particular praise should be directed to all four actors in the play, each of whom pushed themselves to their actorly limits to portray their respective characters with unflinching authenticity.

Although there were a few isolated moments in which acting choices were evidently rooted in direction instead of inner truth and spontaneity, all four actors put forth generally excellent performances.

In short, each of the four actors in “The Fair’s in Town” exhibited an incredible degree of dedication to the material, as well as to their respective characters’ inherent complexities.

Finally, it should be noted that, in terms of its narrative and performative elements, “The Fair’s in Town” closely resembles the classic plays of Tennessee Williams, especially with regard to its limited setting, emphasis on family and the ghostly presence of an off-screen character (in this case, the deceased Jamie).

Nevertheless, in spite of his apparent literary influences, Mattox greatly succeeds in carving out his own playwriting niche through his unwavering adherence to authenticity and all the messy complications that come with it.