Understanding public aid recipents

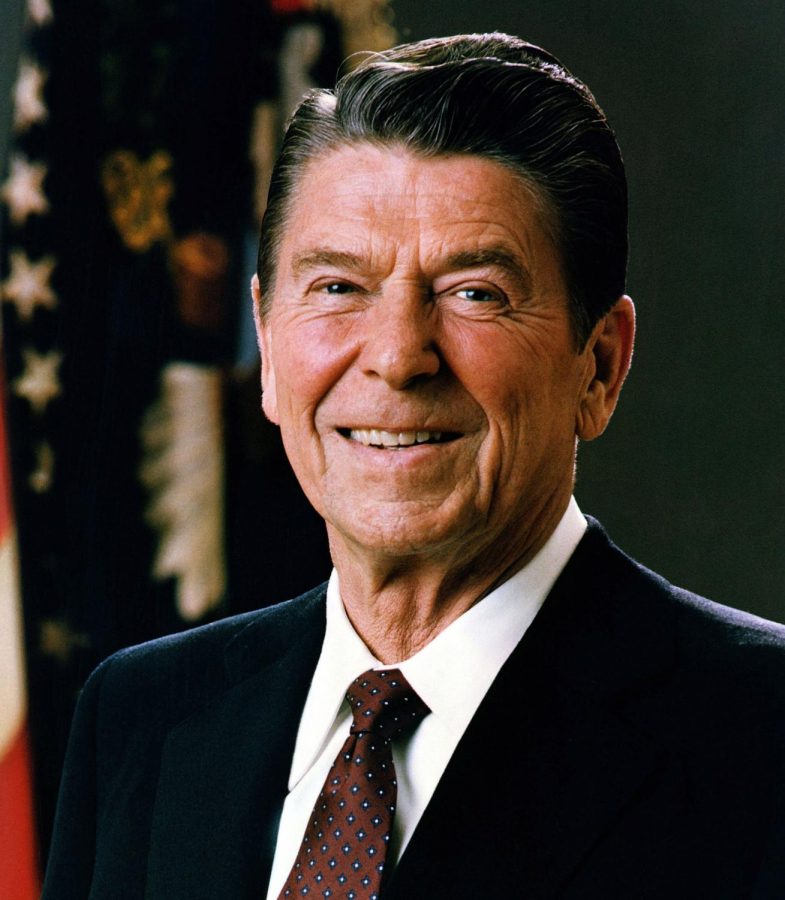

Opinion columnist Abbi Cobb discusses the harmful stereotype “welfare queen,” which was first coined by President Ronald Reagan.

Feb 12, 2018

In considering the contemporary climate of unfavorable perceptions of public assistance and its recipients, it seems impossible to consider the fact that these programs were once valued and widely appreciated within mainstream U.S. culture.

Today, Americans tend to view the recipients of public aid as distrustful, which may come as no surprise when considering the thorough construction of the conception of a typical recipient.

The public’s hostile discourse regarding social welfare policy has been consistently directed toward minority groups and individuals, despite the actual racial composition of recipients.

At the forefront of public scrutiny regarding public assistance are black women. In fact, the widely used term “welfare queen,” coined by President Ronald Reagan, is summarized in a piece on welfare reform proposed by Michele Gilman.

Gilman explains that the phrase was shorthand for “a lazy woman of color, with numerous children she cannot support, who is cheating taxpayers by abusing the system to collect government assistance.”

This depiction of welfare recipients as lifelong, black dependents somehow made its way to the public sphere, where many assume it is representative of all who qualify and utilize the benefits. But let us briefly take a look into what the makeup of aid recipients actually is.

According to the US Census Bureau:

• In an average month, 39.2 percent of children received some type of means-tested

benefit, compared with 16.6 percent of people age 18 to 64 and 12.6 percent of people 65 and older.

• At 50 percent, people in female-householder families had the highest rates of participation in major means-tested programs.

• Of people enrolled in Medicaid, 35.6 percent participated between one and 12 months and 35.3 percent participated between 37 and 48 months.

From these three trends in overall benefit use, it can be concluded that children and their single mothers, receiving for no more than four years, are the real face of American social assistance.

And while black families are disproportionately represented in recipient populations, they do not constitute a majority.

It’s easy to express dissent toward a system of people when the popular rhetoric surrounding it has, for decades, consistently created a deserving versus undeserving distinction among recipients and subsequently blamed undeserving beneficiaries for their disadvantaged position.

This way, by discounting layers of inequality, the dominant perception has successfully defined behaviors and practices of poor, marginalized groups as immoral and lazy, thus contributing to the poverty they live in, if not entirely determining it.

This blame removes any possibility of exterior explanation and vilifies individuals based on their failure to behave according to dominant culture, as if that alone would explain their experiences with poverty.

The assumption that personal characteristics are to blame for receipt of public assistance has elicited punitive and fiscally conservative responses to funding the assistance, and this has seemed especially true in the realm of reforming these systems, making it difficult for the most vulnerable among us to receive the assistance that their families often times require for survival.

The popular debate around this topic has made evident the fact that politicized efforts to shape public opinion have been largely successful in changing the way Americans see welfare recipients and black women, more generally.

The harmful nature of the stereotypical “welfare queen” must be acknowledged as resting both in racialized and gendered stereotypes.